“Sleep is the single most effective thing we can do to reset our brain and body health each day.”

— Matthew Walker, author of Why We Sleep

We can't have a meaningful discussion about how to optimize our mental energy without first understanding how to manage our sleep.

Sleep is the foundation that sets our daily energy levels.

Recently, I had the chance to connect with Nick Littlehales, a professional sleep coach who has worked with numerous top athletes thoughout his career. I read his nice and practical book, and it gave me a new perspective on sleep.

Nick brings a realistic and refreshing approach to sleep optimization. He encourages us to see sleep as a form of active recovery, not just a passive task to get over with.

That insight inspired me to dedicate another month of the newsletter to sleep.

Let’s dive in.

Today’s insights is mainly drawn from the scientific article:

“Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance”

And includes insights from:

“The sleep-deprived human brain”

Today's newsletter

Takeaways:

📉 Consistent short sleep can be as harmful as a complete night without sleep

Sleeping just 5–6 hours per night over several days can impair your attention and reaction time as much as staying up for 24 hours straight.

📆 Recovery from partial sleep deprivation takes time

One long sleep isn’t enough to recover after a period of insufficient sleep. Research shows it can take several nights of 8–10 hours of sleep to restore baseline performance.

🥲Sleep deprivation puts you in a more negative mood

People tend to misjudge their own performance during sleep deprivation. You might feel fine, but key functions like focus, memory, and flexible thinking are likely worsened.

The study in a nutshell:

Today’s main article is a review exploring how lack of sleep affects cognitive performance.

The authors distinguish between acute total sleep deprivation (e.g. pulling an all-nighter) and chronic partial sleep restriction (e.g. regularly sleeping insufficiently).

Across many studies included in the review its clear that sleep loss significantly impairs attention, memory, decision-making, and the ability to think flexibly.

Throughout today’s newsletter, I will draw insights from the other featured article, which is a really nice scientific description of what specifically happens in the brain when we are sleep deprived.

Sleep and sleep loss:

Sleep is regulated by two systems:

Sleep pressure, which builds up as you are awake

Circadian rhythm, which is your internal clock that signals when to sleep and wake

When one is sleep deprived, stress hormones like cortisol build up, blood pressure rises, immunity weakens, and thinking becomes slower and less reliable. Attention is worsened, and the brain struggles to store and organize new information.

There are two main theories explaining why sleep loss effects our cognitive performance:

General alertness loss – One has brief moments of inattention, microsleeps, and one processes stimuli slower.

Prefrontal cortex fatigue – This vital brain area is fatigued, which influences higher order functions like problem-solving, creativity, and decision-making.

Acute total sleep deprivation:

Although most will likely not experience total sleep deprivation in daily life, staying awake for 24 hours reveals just how vital sleep truly is.

Attention and Vigilance

Tasks that require constant focus - like monitoring screens, reacting to alerts, or listening intensely - suffer most. Moments of inattention become more frequent, reaction times become slower and performance becomes inconsistent.

The longer you're awake, the more likely you are to experience microsleeps, which is brief moments where the brain essentially kind of sleeps while you are awake.

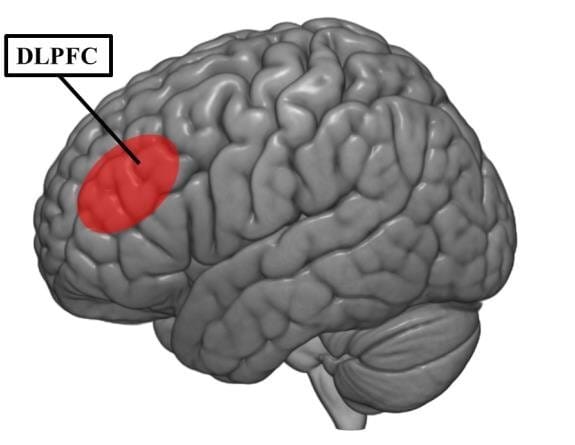

Brain imaging studies show that sleep deprivation weakens attention by reducing activity in key brain areas like the DLPFC, intraparietal sulcus, and visual regions. The thalamus also becomes less stable, leading to lapses in focus.

At the same time, the brain’s default mode network—normally quiet during tasks—stays more active, interfering with concentration and making attention harder to maintain.

Working Memory

Working memory is the system you use to hold on to and work with information in real time - like preparing a response to your boss’s request based on specific information he is giving you. Total sleep deprivation makes this slower and less accurate.

Again the effects on working memory is linked to reduced DLPFC and parietal activity as well as poor default network suppression, and altered thalamic connectivity.

Long-Term Memory

Sleep loss tends to impair free recall - pulling information from memory without cues - more than recognition.

-If you want a nice clear walkthrough of the different types of memory, check out this video.

Chronic partial sleep deprivation:

This is the type of sleep loss most people experience: not a complete night without sleep but consistently sleeping 5–6 hours per night for days or weeks on end.

Even though it feels less extreme, the cognitive consequences are real - and they build up fast.

Attention and Reaction Time

One of the clearest effects is on sustained attention. After several nights of shortened sleep, people get slower and less accurate on tasks that require focus - similar to what happens after total sleep deprivation.

In fact, after just one week of sleeping 4-6 hours per night, performance on reaction time tasks can match the decline seen after staying up for 24 hours.

Higher-Level Cognitive Functions

Compared to total sleep deprivation, fewer studies have looked at how chronic sleep restriction affects complex thinking - like problem-solving, planning, or reasoning. But early findings suggest these abilities might also decline, just more gradually or subtly.

Recovering from sleep deprivation

According to today’s main review study, recovery of cognitive performance after sleep deprivation is possible, though the recovery process between total sleep loss and chronic partial sleep deprivation is different.

Total Sleep Deprivation

After a complete night without sleep, one long recovery night (around 8–10 hours) seems to be enough to restore basic cognitive functions - especially attention and simple reaction time.

Chronic Partial Sleep Restriction

Recovery from multiple nights of insufficient sleep seems to be slower.

One good night of sleep is not enough.

Some studies show that even after three full nights of recovery sleep, some aspects of performance - especially sustained attention, which I find very important in my day to day work - may still be below baseline.

One possible reason why recovery from partial sleep deprivation takes longer than from total sleep deprivation is that, during partial sleep loss, the brain tries to compensate and keep performance as steady as possible. This turns out to be very straining for the brain.

With total sleep deprivation, on the other hand, the brain kind of “gives up” on maintaining performance, which, might put less overall strain on the system, compared to being partially sleep-deprived for multiple days.

Sleep and emotions

Sleep deprivation disrupts the brain's emotional balance by impairing reward and regulation systems. For example, after a bad night's sleep, small frustrations - like a slow email reply - can feel disproportionately upsetting. Reduced dopamine receptor availability, along with weakened frontal control, makes it harder to manage emotions.

At the same time, sleep loss prevents the overnight reset of adrenergic tone, leaving emotional networks in a state of heightened arousal. This overactivation contributes to emotional overgeneralization and prolonged stress responses — like staying upset for hours after a minor disagreement.

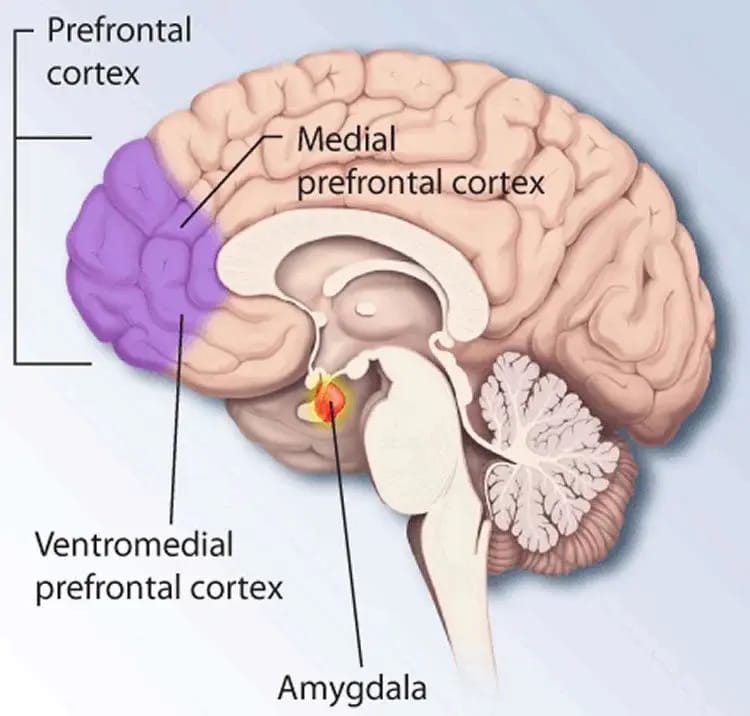

The amygdala becomes more reactive to negative stimuli, while the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) loses its regulatory grip, leading to increased emotional instability and threat sensitivity.

Individuals with high anxiety traits are especially vulnerable, experiencing elevated anticipatory anxiety and arousal even before encountering emotional triggers.

-If you'd like to hear one of the most well-known sleep scientists explain the connection between sleep, the amygdala, and the prefrontal cortex - and how this relationship shapes our emotions - I highly recommend giving this short video a watch.

Individual Differences

Its important to note that there are some individual differences.

Some people are just more resilient to sleep loss.

This may be due to trait-level differences in brain function.

For example, fMRI studies show that people who are less affected by sleep loss have distinct patterns of brain activation in the prefrontal cortex even when well-rested.

What can we learn from this study?

For young ambitious professionals, it seems clear. Sleep loss has direct and instant consequences for our ability to perform optimally.

A single night completely without sleep significantly weakens your ability to focus, remember, and think clearly.

The good news is that the recovery from this type of extreme sleep loss is actually quite quick.

However, recovery from the much more likely scenario of getting insufficient sleep over a longer period, is slower and cannot be restored over a few nights. And unfortunately, the consequences to your performance from this type of sleep loss is just has clear, and besides the performance decline, it might put you in a less positive mood.

We must however, acknowledge individual differences. Some people are more sensitive to sleep loss than others. So maybe you can perform in the short run while being sleep deprived, but I feel pretty confident, that we all need to respect our sleep in the long run.

I know I at least try to take as much care of my sleep as possible, as I feel the direct results on my everyday performance.

I’m currently building a 7-day sleep program with professional sleep coach Littlehales.

To make it even better, I’d love a few of you to try it out and share a bit of feedback.

If you’re interested, just let me know - I’ll reach out with the details.

|

Until next time, Nicolas Lassen |

Disclaimer: The above is mainly based on the article “Sleep deprivation: Impact on cognitive performance” by Paula Alhola & Päivi Polo-Kantola and “The sleep-deprived human brain” by Adam J. Krause, Eti Ben Simon, Bryce A.Mander, Stephanie M. Greer, Jared M. Saletin, Andrea N. Goldstein-Piekarski & Matthew P. Walker and aims to provide key takeaways and a condensed overview of its content. While the essence is drawn from the original article, some parts have been simplified or rephrased to enhance understanding. Please note that we at, OptiMindInsights or any other potential writers or contributors to our summaries, do not accept responsibility for any consequences arising from the use of this summary. The information provided should not be considered a substitute for personal research or professional advice. Readers are encouraged to consult the original article for detailed insights and references. The summary does not include references, but they can typically be found within the original publication. Always exercise due diligence and consider your unique circumstances before applying any information in your personal or professional life. We refer to the creative commons for reproducibility rights.